Over 300,000 years of adaptation, the human body has internalized the fact that it cannot afford what it doesn’t use regularly. It takes frequency of use as a proxy for “need”.

In neuroscience you can see this through synaptic pruning. Synapses that are seldom used are gradually removed, while frequently activated connections are strengthened.

This "use it or lose it" principle ensures that neural networks become more efficient and specialized over time. This mechanism underlies much of human learning and growth.

As the use of AI powered tools becomes ubiquitous, what skills are we using less and hence at risk of losing? What are we willing to no longer be able to do?

AI as a Tool

There appear to be primarily two popular metaphorical buckets for how AI will impact the skills of knowledge workers.

The first likens AI to a car for the mind (building on the notion of “computers are bicycles for the mind”). In this world, AI brings automation and machine leverage to human activities, especially knowledge work for now, beyond our wildest dreams.

Mimicking the developments that started with the steam engine, the freedom to no longer have to rely on human (or animal) power was not mourned as it was never considered a valuable activity.

Certain jobs were and will be disrupted but the net benefits are clear. As long as you can prompt the chatbot effectively, you never need to look under the hood (pun intended).

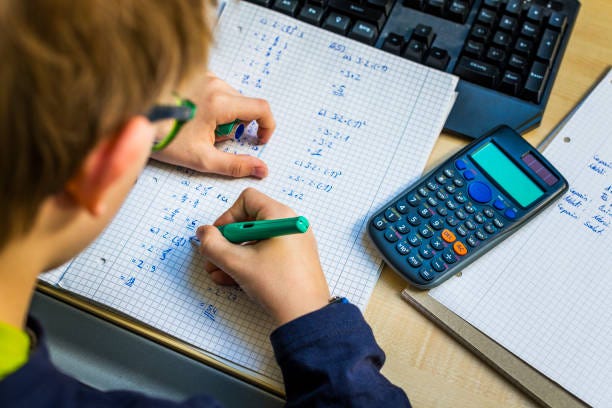

The second bucket compares AI to calculators - primarily centered around what is known as “cognitive offloading”. In this mental model, the technology automates a core skill (basic arithmetic) which many deem important but not critical. As such, we continue to insist that our children learn that basic skill (most education systems prevent the use of calculators until middle or secondary school).

Nevertheless, it turns out that higher-order thinking in the form of structuring and solving problems is much more important than basic arithmetic. Using a calculator turns out to free humans to solve more “interesting” and valuable challenges.

The common thread across these two buckets is the underlying assumption around AI solely as a tool. It’s something that we are using to generate certain outputs. While useful, this metaphorical paradigm is not sufficient.

A New Paradigm for AI & our Minds

The ubiquity and scale of AI adoption require us to think of it through a different lens - that of human health & longevity. AI is getting integrated so rapidly into the fabric of our reality that it is best thought of as more than just a tool.

One of the key indicators of human health is cholesterol level in the blood. While most people only start worrying about their cholesterol later in life, it’s common knowledge that the buildup of cholesterol is largely affected by two factors across one’s lifetime: diet and exercise. In the same vein, with AI it’s less about if or not you use AI but how much of it you consume and what you do to stay “fit”.

As we integrate AI more and more into our lives, two critical factors matter. The first is the kind of content we consume to build our expertise. You can think of this as your “informational diet”. The importance of this diet is growing exponentially as the world gets flooded with “slop”.

Second, as AI commoditizes many outputs, the value of process paradoxically begins to increase. Like exercise, the desirable difficulty embedded in learning and knowledge acquisition is critical. Take the elevator too often, and one day, you may find yourself unable to climb even a single flight of stairs.

Building a treadmill for your mind

Without a crystal ball, the best approach to deal with this rapid change is to lean into this new paradigm and prioritize a good diet and exercise for the mind.

There are 5 key principles to make that happen:

Lean into developing deep expertise, and leverage AI to accelerate that process. There is a misguided notion that AI devalues experts. In fact, AI is a multiplier. For those with deep knowledge, it accelerates insight and execution. For those without it, it is a poor crutch to mediocrity. Leverage AI tools to go deeper into more difficult and niche areas within your domain expertise. Focus especially on your capacity to frame better questions.

Prioritize process over product. The received wisdom at work (and at school) has been to focus on the final output of an assignment. Under this paradigm shift, we need to emphasize the process. You need to think of work and learning as exercise and focus on the “reps” you put in. Lean into the friction needed to create the mental work and synaptic connections. Let the AI help you do more reps with infinite feedback, but do the work yourself.

Embrace a Stochastic Mindset. In the past, our relationship with technology has assumed it was giving us deterministic outputs (“the right search result’). We must now shift to a mindset that “embraces variability and uncertainty” i.e. getting comfortable with tools that provide “drafts or suggestions rather than definitive answers”. We do this by adopting a more questioning stance that leverages our expertise (see above).

Harness your attention. Ironically, it was a paper titled “Attention is All You Need” that kicked us off down this LLM-filled path. It proposed a new architecture (the transformer”) that changed how machines handled information. This shift has further accelerated the decline in our attention spans. In the current setting we are in today, one of our biggest problems is “misallocation of attention”. Push yourself to stay and struggle with ideas and topics for longer. Less “BookTok”, just plain old books.

Keep it away from the kids (for now). In a strong parallel from the longevity space, where we are still finding out the effects of things like additives and microplastics on our bodies, we need to prioritize protecting the most vulnerable. The reality is we still don’t really know what impact AI will have on our minds and faculties. I’m cautiously optimistic, but that doesn’t mean we should be bringing into the lives of young children with very malleable brains. Let us avoid what happened with social media and screens (so: “no”, don't bring it into the curriculum of 4 year olds)

In antiquity, Socrates feared that writing would erode memory, warning that it might give people the illusion of wisdom rather than its substance. While history proved him partially wrong, his concern remains strikingly relevant.

Today, we face a far more powerful shift: machines that can not only store but simulate thought. If we outsource too much cognitive effort to AI, we risk not only forgetting but forgetting how to think.

True learning, true thinking, must remain embodied—slow, effortful, and deeply human. Unless we take deliberate steps to cultivate and challenge our minds, we may one day look in the mirror and find not just faded skills but a dimmed capacity to think altogether.

I hope you enjoyed the last edition of Nafez’s Notes.

I’m constantly refining my personal thesis on innovation in learning and education. Please do reach out if you have any thoughts on learning - especially as it relates to my favorite problems.

If you are building a startup in the learning space and taking a pedagogy-first approach - I’d love to hear from you. I’m especially keen to talk to people building in the assessment space.

Finally, if you are new here you might also enjoy some of my most popular pieces:

The Gameboy instead of the Metaverse of Education - An attempt to emphasize the importance of modifying the learning process itself as opposed to the technology we are using.

Using First Principles to Push Past the Hype in Edtech - A call to ground all attempts at innovating in edtech in first principles and move beyond the hype

We knew it was broken. Now we might just have to fix it - An optimistic view on how generative AI will transform education by creating “lower floors and higher ceilings”.