Memory & Models: The Power of The Analogies We Live By

Or the future of tutoring if your brain was not a computer

We often think of memory like retrieving a file on a computer. You just need to find the folder, double click on it, find the image, click again, and voila.

There it is - the memory of that family vacation on the beach, your first day at school, your little one’s first steps.

Ofcourse, that’s not how human memory works. Human memory is a lot more complicated than finding a file on a computer, but metaphors help us simplify complicated and messy topics.

And memory is very messy. When we “recall” a memory it’s not like “pressing play on a tape machine; it’s like pressing play and record together”. The act of recalling a memory actually alters it directly. You can’t have the exact same memory twice.

The metaphors we live by determine how we think about and experience the world. The way we think about memory and the brain in turn greatly influences how we think about knowledge and by extension learning.

For example, we tend to believe that student memories are all “stored” in their minds, and we just need to find a better way to collect them and sort them. We just need to help our students and learners connect all this new information to stored knowledge. We are thinking of the human brain as a computer.

The analogies we use are helpful in understanding the world, but they are by definition limiting, and sometimes harmful. The analogies we use define our ambition and how we solve a problem. As such, we risk mistaking the map for the territory.

The current buzz about finding an “AI tutor” all seems to rest on this important analogy - the mind as a computer. When we talk about reforming education with AI, we think of the human brain as a computer but what if that is the wrong analogy.

The “brain is a computer” analogy attempts to reduce all cognition to calculation. As such, the AI tutors we are developing attempt to help students use better “algorithms” as they calculate their way through the world’s problems.

Of course the underlying set of assumptions & generalizations for this to be true is as large as the latest Llama model but let’s keep it simple and point out three quick ones:

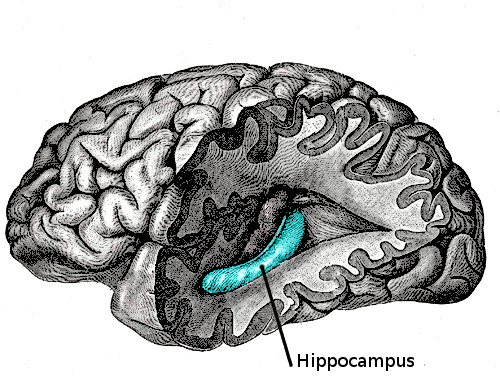

First, it assumes students are aware of all the variables at play when they think about a problem. However, to go back to memory for a second: in many instances we respond to present situations according to stored memories we aren’t even aware of consciously.

Second, unlike a computer performing calculations, a human brain’s performance is greatly affected by its interactions with its surroundings - perceived and real. The field of ecological psychology assumes that humans are always in constant interaction with their environment as part of a dynamic system. Under this paradigm, the push is for “tutors” to think more as learning designers than leaders of learning.

Third, and as the late Ken Robinson often liked reminding us, our bodies are more than vehicles to transport our heads. In fact, the theory of embodied cognition holds very convincingly that “learning is moving in new ways”.

The Embodied Research Design Laboratory at UC Berkeley has shown with their “Mathematics Imagery Trainer” that we can teach children mathematics much more intuitively by helping them associate it with new ways of movement.

In fact, we know that some of the world’s great mathematicians from today’s Terrance Tao to Einstein and Poincare learned math with their bodies at some point.

It would take more than a single article to clearly identify what it would take to build an AI-tutor assuming that the brain was not in fact a computer. Nevertheless, we can start with the following two improvements.

First, for tutors to be effective they need to be able to better understand a learner’s context, background and surroundings. A big part of this lies in creating better assessments and will naturally be quite challenging to do for the youngest and most vulnerable learners.

Second, we need to move beyond the notion that effective tutoring can only happen one-to-one through direct instruction at a desk. We should create tutoring experiences that allow for new ways of movement and learning in small groups and with peers.

To unlock a better future for learning, and to imagine better visions for the tutor of the future: we need to move beyond the constraints of some of our analogies, especially thinking of the mind only as a computer.

I hope you enjoyed the last edition of Nafez’s Notes.

I’m constantly refining my personal thesis on innovation in learning and education. Please do reach out if you have any thoughts on learning - especially as it relates to my favorite problems.

If you are building a startup in the learning space and taking a pedagogy-first approach - I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, if you are new here you might also enjoy some of my most popular pieces:

The Gameboy instead of the Metaverse of Education - An attempt to emphasize the importance of modifying the learning process itself as opposed to the technology we are using.

Using First Principles to Push Past the Hype in Edtech - A call to ground all attempts at innovating in edtech in first principles and move beyond the hype

We knew it was broken. Now we might just have to fix it - An optimistic view on how generative AI will transform education by creating “lower floors and higher ceilings”.

The article stirred an old memory of when I first read “Les Maîtres mosaïstes" by the French writer George Sand (pen name of Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin). In it, she poignantly states: “Le souvenir du bonheur n’est plus du bonheur; le souvenir de la douleur est de la douleur encore.”

Her statement encapsulates her contemplative insights into the lingering effects of memory..

Much like the experiences students have with education, where the joys of learning may fade into melancholy, the memories of challenges or achievements while studying continue to evoke strong emotions—be it the pride of success or the lingering sting of past struggles..

Thank you for the evocative reflections Sir..!

I agree with you, Nafez. The late Ken Robinson emphasized that our bodies are more than vehicles to transport our heads, and by embracing the theory of embodied cognition, AI can design Tutor features that integrate motion tracking, VR, and AR to create dynamic, movement-based learning experiences. These AI-driven tools enable students to physically engage with educational content, adapting in real-time to personalize and enhance the learning journey.